Apenas el Sol (Nothing but the Sun) had its North American premiere at Hot Docs this week; it is Arami Ullón‘s second feature documentary. The film ties into the growing plight of Indigenous people everywhere who are working towards the conservation of their language and culture

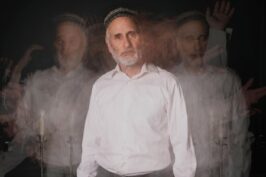

Facing the consequences of a violent uprooting, Mateo Sobode Chiqueno has been recording stories, songs, and testimonies of his Ayoreo people since the seventies.

In an attempt to preserve fragments of a disappearing culture, Mateo walks across communities in the desolate Paraguayan Chaco region, and registers on cassettes the experiences of other Ayoreo who, like him, were born in the vast forest, free and nomadic, without any contact with white civilization, until religious missionaries forced them to abandon their ancestral territory, their means of subsistence, their beliefs, and their home.

Apenas el Sol is required viewing. From its opening minutes, one is drawn into Mateo’s words, and his world. Over the course of the film, we come to know how he and many other Ayoreo people became displaced from their ancestral home in the Paraguayan forest.

Mateo speaks to many other members in the community; allowing them to share their experiences. Their conversations are very moving. Even in situations when Mateo may not agree with others’ way of accepting their fate, he allows them the time and space to express their points of view.

There is a lot to appreciate in Apenas el Sol, from Mateo’s strong yet quiet screen presence to the visual composition and pacing of the film.

The people, their stories, the nostalgia for a lost home, the feeling of not belonging, and Mateo’s own wish to preserve aspects of the culture, all make for a very emotional film. I was deeply moved by it, and this is also a compliment to Ullón’s direction and the care she and her crew put into making the film.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Arami Ullón about the making of Apenas el Sol, her connection with Mateo and his community, and the bigger themes the film addresses.

Off camera (so to speak), Ullón’s also explained how it was never the purpose to film a documentary about the Ayoreo people who continue to live in the forest voluntarily; the way their ancestors have lived since time immemorial. They should not be contacted; something Mateo also mentions in the film.

We did not get to speak much about how some audiences, including critics, have commented on how ‘deep and rich’ the Ayoreo people’s stories are. This is a very Eurocentric point of view, which Ullón made sure to remind us that because we do not understand the languages of Indigenous people, we cannot assume they are not rich in meaning. In fact, most Indigenous languages are richer than other languages around the world.

These are some of the reasons that make it even more important and necessary for films like Apenas el Sol to be made. Part of what I appreciate about the film is learning how Ullón and crew took care to work alongside Mateo and his community to make a film that is theirs also. Here is hoping they are able to show the film to them in the near future, and that other audiences also get to see it worldwide.

You can find more information about Apenas el Sol (Nothing but the Sun) here.