In Dahomey, director Mati Diop achieves something rare and profound: she transforms a historical documentary into a poetic meditation on colonial violence, cultural loss, and the fragile act of restitution. The film follows the return of 26 royal treasures, looted from the Kingdom of Dahomey in 1892 by French colonial forces and finally repatriated to their homeland, Benin, in November 2021.

Through a beautiful blend of visual poetry, evocative soundscapes, and meditative debates among Beninese students, Diop crafts an experience that asks not only what restitution means but also what it should feel like – for both the nation receiving its cultural heritage and the nation forced to return it.

Diop approaches the treasures as something much more than objects. As these artifacts set off from the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, the camera follows them as protagonists in this story, carrying histories that speak to their cultural and spiritual significance. Diop and her sound team, including Nicolas Becker and Cyril Holtz, achieve this by carefully crafting a soundscape where silence also becomes expressive. The quiet moments around these artworks are as loaded with meaning as the voices of Beninese students or the artefacts’ own narration. Their silence is an embodied presence in itself, as though the objects, after a century of silence in Europe, now exist as witnesses of colonial theft.

The film’s soundscapes also help bridge the past and present in this narrative. Diop’s focus on creating an “audible silence” through sound editing evokes the suppressed voices and histories of the Dahomean kingdom. These layers of ambient sounds, whispers, and moments of quiet reflection evoke the complexity of restitution. The absence of sound around these artifacts mirrors the absence of their culture from its homeland, reminding audiences of what it means to be forcibly silenced.

This approach speaks to the thematic depth of Dahomey, a documentary that reads as a “fantasy documentary,” combining fact and feeling in ways that blur the line between history and mythology. Diop animates these artifacts, giving them with a voice that embodies both loss and resilience. The film’s voiceovers suggest the artifacts as having their own consciousness, with lines like “[I] lost myself in my dreams” and “I didn’t expect to see daylight again.” This personification turns the artifacts into symbols of stolen identity and silenced cultural expressions, mirroring the experience of people who have been wounded, displaced, and rendered voiceless over decades of exile. Diop’s choice to evoke a voice from the artifacts asks us to see them as beings, not objects – a choice that depicts the incalculable loss experienced when cultural heritage is severed from its people.

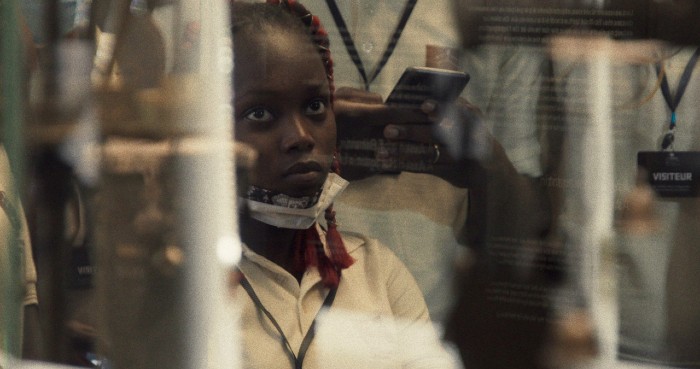

Mixed with these reflective moments are scenes at the University of Abomey-Calavi, where young Beninese students grapple with the arrival of the artifacts, confronting complex questions of cultural ownership and identity. Their discussions show both the pride and ambiguity surrounding this homecoming. Having grown up in a Benin redefined by modern borders and transformed by its own evolution, the students express a keen awareness of how their nation, and even their identity, has changed in the artifacts’ absence. Their words raise powerful questions: Do these objects still “belong” to a people who have grown up without them? Can physical repatriation truly heal a fractured cultural lineage? Through their conversations, Dahomey captures an intergenerational negotiation of meaning. It is a reflection of how history, when interrupted by colonialism, leaves behind a void in need of new interpretations.

In Dahomey, Diop does not shy away from the uncomfortable truth that these treasures have been altered by their long life in a far away land. While their return is hailed as a historic act of restitution, the film aptly raises the question of whether that alone is enough. Diop’s meditative style suggests that restitution is far more than an act of physical return. It is also an invitation to reframe a people’s relationship with their past. It presents a chance to ask what has been irretrievably lost along with the artifacts. For the people of Benin, who have preserved their cultural continuity in other ways, the repatriation of these royal treasures brings both joy and ambiguity. Diop portrays this duality through images that merge past and present, connecting the lingering shadows of colonial theft with the hopes and complexities of reclaiming these objects.

At the heart of the film is Diop’s collaboration with Haitian writer Makenzy Orcel, whose poetic contributions amplify the film’s themes of diaspora, displacement, and shared African history. Orcel’s background, like that of many Haitians, is tied to the descendants of enslaved Africans from the Bight of Benin and West Africa. His voice reflects a transatlantic conversation, echoing how the diaspora, too, has been shaped by the legacies of colonial violence. Orcel’s words, inspired by Diop’s footage, add layers to the film’s emotional poignancy, turning the film into a collaborative reclamation of narrative. Through this dialogue between African and diasporic voices, Dahomey goes beyond its national context to reflect on universal questions of self-determination and identity within the Black diaspora.

In the end, Dahomey is not a simple narrative of reclamation but a cinematic meditation on what it means to restore stolen heritage in a way that honours both history and the future. Through its beautifully layered storytelling, Diop’s film invites us to consider how the physical return of objects does not necessarily fill the void left by their absence. The film asks us to imagine restitution not merely as a transaction but as an act of restoration, a way to attempt to reconnect with a lost wholeness, no matter how imperfectly. Through Dahomey, Diop not only records a historic moment; she invites us to confront the ongoing legacies of colonialism and to question whether restitution can truly undo the past or merely provide a path forward toward healing. The film, like the artifacts it follows, holds a powerful, unresolved tension that lingers long after the credits end.