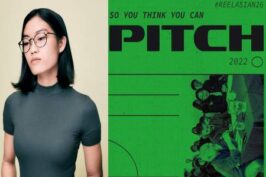

Currently residing in Los Angeles, Yuchi Ma is a female filmmaker from Beijing, China. Her short film Red Threads (我很爱你) won the Grand Jury Award in the Experimental Shorts section at this year’s Slamdance Film Festival. This piece captures the experience of a Chinese Parachute Kid living in the United States.

Initially inspired by the Tang dynasty poem ‘Song of the Wanderer’ and ‘Red Threads’ as lines of fate in Chinese culture, Yuchi combines of Live-action Cinema, Sims 4 Machinima, Browser/Webcam framing, and Sewing to perform a filial ritual by building a simulation of her American, her Chinese, and her Chinese American experience. Existing as “psychologically nowhere,” Sims 4 brings Yuchi’s Parachute experience into a true state of being “psychologically everywhere.”

After premiering her award-winning short film at Slamdance, Yuchi and I connected virtually. We spoke about living in the US and the start of her career in the arts.

HM: Let’s start with talking about you moving to the USA for your studies which also led to you choosing your current career.

Yuchi Ma (YM): “I am a Parachute Kid. If you’re unfamiliar with the term, ‘Parachute Kids’ are unaccompanied minors who are sent to study in the US or other Western countries, as early as first grade. For me, my parents sent me to go live and study to the US when I was eleven turning twelve. At the time, I stayed with a distant relative who became my host family. I kinda went through your usual steps through the steps of assimilation, and different things you experience… sort of an immigration journey, in a way. I ended up doing middle school and high school in Texas, and eventually, I came out to LA for college and grad school. And that’s sort of where I started making work for myself.

Currently, I will say I am a multidisciplinary artist, based in LA. The reason for saying I’m a multidisciplinary artist instead of just a filmmaker because I don’t know if I necessarily feel like my work belongs in the narrative, or at least it doesn’t belong in the commercial film world. I’m experimenting my way into the art world but oftentimes I find my content to be more narrative or emotional than pure conceptual or theoretical style. And so I would say that if I were to really identify my practice, in a way I feel more like a video artist and I have my specific themes that I’m interested in and working more toward video instalation… or to find a way to sort of physicalize the experience of watching the video and making it make some sense in relation to this specific cultural experience.

HM: So maybe talk a little bit about working with video and trying to visualize this experience because the way that I experienced your short film, which is really beautiful, Red Threads (我很爱你) was, I almost felt like, it was a little bit of a mix of a poem… peppered with a lot of personal stuff. And I’m curious about that process of coming up with the narrative or the language you want to sort of visualize in your work.

YM: Thank you. I think that you’re definitely right in that it feels more like a poem than a narrative story in the traditional sense. I’ve always been drawn to poetry and poetic filmmaking, and also I do feel very influenced by my mother, who’s also an artist. She’s a choreographer and a dancer. And I think that growing up, watching her work has influenced me more than anything else. And in that sense, when I make videos, I feel that I’m attempting to dance with my visuals or with my videos in a way, which I think also lends itself very well to poetry. But in making this specific work, some of the things I was thinking about and researching are ‘how do I sort of represent this intercultural experience?’ Something that’s for the in between and not necessarily one or the other. How do I know that? And I was kind of struggling to put it in the way of… the Western lexicon of don’t make the tradition for making structure and felt like I needed to find something of my own, whether that being just to be very personal and just to follow my own will completely. And I think maybe this is a part of me defining what videomaking means to me and why it’s so centered to my practice. And I think there’s a lot of things about how video is sort of the way you remember certain memories is not necessarily how the memories was, but it’s how you’ve decided to look back into it.

And being in a position where I’m always in between or I’m always away from one or the other thing, it becomes a very important way for me to stay attached or keep track. And I think that I could give a lot of maybe more theoretical answers to reference what video making is, but at the end of the day, I think that videomaking for me is to love and it’s to express love. And when we talk about the gaze, it can be so complicated, right? Because you are in a position of power looking upon the other. And I think for me, that this practice is a practice for me to look at things with love and to express that. And so I think for that reason, this film and all my works, which are very personal, sort of, I think, come off with this feeling.

HM: Can you talk a little bit about the title of the work, Red Threads (我很爱你)? It can give us a lot of visuals as well based on that, maybe let’s start with the title.

YM: So the full title of the work is actually Red Threads (我很爱你)… For those who don’t know Chinese, they may just think that it’s a translation of ‘Red Threads’, but they’re two different terms. The Chinese portion of it means ‘I love you very much’. And so just to start off with the first layer, Red Threads, as you can see, is weaved as a primary visual symbol throughout. Traditionally, in Chinese culture, red threads are seen as the symbols for lines of fate.

And so you know how in Western culture people sort of have cupid going around shooting arrows and fall in love? In traditional Chinese mythology, it’s this older man who’s a god who ties threads around people’s fingers, people who are fading together. And so, because of this piece, relates so much to how I feel about not being with my mother, not being with my homeland, and then being a Chinese person where filial duty is such a heavy part of our identity, I saw these lines of fates, these rest threads, as sort of this attempt to close that distance, but also contemplate what kind of pressure or whatever it is really applying to this specific cultural experience. But ultimately, I wanted to sort of express gratitude to my parents who’ve made a choice for me to send me abroad. And the distance and isolations have been created, which is why the Chinese portion of the title says ‘I love you very much’. Because especially, I think in the scenes where the red threads were wrapping around everything personal cultural objects and then eventually around the person who’s supposed to be me in the scene. I think for that there’s both a feeling of intense love but also almost close to suffocation, in some ways, because of the way you’re wrapped.

And I think that your attachment to your filial duty and family dynamic can at times really feel that way. But at the end of the day, I wanted to let them know that ‘I do love you’ and this is a gesture of love for me. And then obviously, I chose to with the English and Chinese meaning different things, a lot of people who only speak one language kind of lack the cultural context. But that was part of my intention along with a lot of other aspects in the film with the way they’re translated or the music keys that are used. I think that it offers sort of a cultural key to the person with similar experience. And so, in a way, this piece is only fully felt or only able to be fully felt by somebody who was also from a similar cultural background. But that was definitely my original intention because first and foremost, I made this piece for myself.

HM: Right. Yeah. I think it’s great that you explain it that way. And I do understand the nuances of having the dual meanings… and I do appreciate the fact that sometimes you create work that is specifically for you and people like you. But it also has, because those of us who speak English, we can still pick up a lot of the themes in the work, it’s still quite relatable at the same time. So again, playing with this duality of who is the intended audience, at least that’s how I experience it.

YM: Definitely, and I think that having always made personal work, I’ve definitely gone through the journey and it’s still going through this ambivalence you feel where it can feel so self centered and so closed off or shallow in a way. But I think that whenever I do feel that way, the statement that really inspires me and I always come back to originally from, I think, like the Kamahi River Women’s Collective was that the personal is political. And I think that while making personal work, it is important to recognize that you are not an isolated individual and you have a lot of identities and relationships that ties you to the larger environment. That ultimately these things are all related to the bigger world and political. And so in that sense, I think with my personal practice, I’m always trying to find a way to how to extend it also to other individuals so that we can all relate to it together.

HM: Yeah, especially being in a setting where you are in the [United] States, where it’s quite diverse as it is here in Canada, where I live. Where there are a lot of experiences that are very personal, but at the same time translate to other people that are not of our culture or ethnic group. I wanted to talk a little bit about the Sims world in the work and what it was like for you to work in that because I picked up from the film or the video that you weren’t sure about creating your mom in the Sims world and what that experience was like.

YM: So with the Sims, I’ve always really loved playing Sims, even as a child. But whenever I played, though, I was never interested in creating completely fictional characters. I was always more interested in playing with people I already knew in my real life. And so thoughts recreating their virtual characters through the game space. Because it was just like stress relieving entertainment for me for so long, I didn’t necessarily think of it as part of my practice, although with this piece it certainly is becoming a part of it. I do find it to be a very apt metaphor for my American experience so far, where I’ve been here since I was eleven, turning twelve.

And in terms of culture assimilation from feeling like this place is not somewhere I can be into really having a lot of friends and community and time and memory spent shared here. What here [USA] means to me has really transformed, but at the same time, I’ve always been a student visa, which is a very temporary state of existence. And so in that sense it kind of feels like my parents paid a lot of money to US education institutions of what various sort and for all Parachute Kids to sort of gain this American experience but to experience being American means that at the end of day you’re still not American. And so in it’s kind of like a life simulation game, which is what Sims is, and I had been unconsciously creating all of my American friends in Sims. I was just like that’s just so weird how I went hand in hand and especially every summer when I met in China I wasn’t with my friends. Like I would play with their Sims. It was kind of like such a weird mix. And then subconsciously, I’ve always been afraid of making my parents in the Sims because I think part of it is that this was a space of escapism for me in some ways, but also because this life that I have in America feels so separate from the life that they live in China and the life that I used to know.

And so, I think very literally the bring together of the two is sort of like something I have to face in my future in the next step. I think in a lot of ways there was a lot of fear that and then also one quote that I used in the video to sort of address this feeling is something as a conversation exchange that happened between my mom and her mom because I said that before my mom is a dancer and so when she was younger her mom would want to come watch her perform and my mom would always say, “if you do come, don’t let me know because if I know that you’re here watching me I can no longer dream on stage”. And I really felt for that sentiment even in just the Sims making and in the game making aspect. But by initiating building my mom’s Sims [character] and bringing her into this world in this project this is sort of also my attempt at expressing that love and expressing understanding my duties to sort of that to bring the two together because this is who I am and I cannot be one or the other. I have to be both.

HM: Yeah, I mean, especially because you’ve spent that much time now studying abroad. It’s kind of hard to not be part of that culture in US Society. And congratulations, I meant to tell you on your award at Slamdance. That’s really cool! So tell me about your experience with bringing your work to film festivals like Slamdance, and what are your plans with moving forward with this project but then maybe future ones as well.

YM: Yeah, for Slamdance, I’ve always been wanting to submit to Slamdance but this was my first time actually submitting. When I made the work I thought, oh, it would be really cool if I could go to Slamdance with this, but I didn’t expect it and I certainly did not expect to win. And so I would say those were all kind of like a double egg yolk, like a very big surprise. Right before Slamdance, I had been doing a lot more art related stuff and.. about how the original version of Red Threads is actually a video sculpture. And so I’d been exhibiting a lot more in art spaces and kind of like feeling like whether I want to anchor myself in that more.

But Slamdance was such a great community. I think you could really sell like the it is filmmakers for filmmakers… And I felt very lucky to be able to share this film with the people there and to screen it in such an inclusive community. I think that this experience has made me realize that I do want to continue to make work that can also be shared in a screening space. Even if I don’t know if I mean, there’s so many ways to define being a filmmaker. Even if I feel more like a video artist, I think it still lends itself to screening spaces. But I just feel like because the emotions is so important to my work, the way that somebody focused on what they’re watching in a gallery space versus in a screening space is very different. And so, because you’re able to focus so much more emotionally in a screening space, I felt that it was important for me to keep creating work that can live in both of these spaces.

HM: Yeah, I like Slamdance. I’ve gone once and I really enjoyed that energy… So you brought up the idea of how we may experience video work in a gallery versus a cinema, for example. And now that you’ve experienced Slamdance, what is it that you’ve learned… What is it that you appreciate of one and the other?

YM: I think kind of like what I was saying. I think you have screening spaces you’re really in a dark room with the sound as loud as the way it should be there’s around you. There are no people walking. It’s dark. You’re just focused on the video. So that attention that you give to the piece in a screening space lends itself much better emotionally.

In a gallery space, I’ve also received a lot of really meaningful feedback from people who really connected with the work. But I think that it depends on when they’re watching it, because during opening is so loud and a lot of people socializing, I don’t necessarily think for anything that’s durational. It’s not the best. But what I do like about the gallery space and why I’m also working on expanding my practice continuously in the art world is that I want to be able to find viewing experiences for my film that are more than just watching sort of in a screening space. I want to be able to physicalize that video and that experience in some way. And so the video sculpture piece I made that accompanies this has a lot of its own significance as well in terms of the fact that it’s not projected, it’s selected to be on a computer screen because my mom and I mean communication over these years, especially the pandemic because it’s mainly done for the video.

So there’s video chat, so there was a lot of considerations about the screen like ‘what does that sort of mean?’ And we sort of see as a portal but really it’s not a portal necessarily because the existence of the screen reminds you that the separation does exist and that looking onto is sort of this interface of how it reflects how both of us feel individually. But to be a portal, there’s sort of that block in the communication, which is just something you’re not going to get from a screening space because everyone’s film is projected in the same way.

Similarly with the shape of the sculpture, I think it adds another layer of personal meanings with a lot more sewings of the actual poem that was used in different languages. So I think it speaks to, again, the different languages translation aspect but also the fact that I had intended a sculptural form to be a deconstructed version of my own body that there are certain results and vulnerability that’s related to that.

And so it’s kind of hard to say, but part of my current interest in my practice is that based on this is a theory book that was written by writer actually from Canada named Laura Marks. The book is called The Skin of the Film and it kind of talks about how certain intercultural experiences are felt or expressed through senses more than just a visual. And so that was something I was super interested in. And then again talking about that specific culture key that these films act as some type of fossil and that when someone with the correct key cultural key comes upon it, it starts to date and then become its thing. And so because I was so interested in that and being able to touch the video and touch that memory in some sense, I found that the video sculpture or like video insulation type of experiences lends it to me sort of experimenting more.

HM: Yeah, that makes sense… So yeah, very interesting concepts as well that you’re bringing up in how you can still work with video, but also make it a little bit more tangible. Right? In terms of being three-dimensional. So if this is your future direction, what are you working on right now in terms of your project?

YM: It’s nothing super concrete, but I do have some ideas. Recently at a show I went to someone I was just speaking about this specific experience and someone asked me if I knew of this term that I’m not sure if there’s a direct English translation, but I would translate it as ‘mother tongue shame’ in that there are specific experiences or things that you have no problem saying in English but you embarrassed talking about it in your mother tongue. Whether it’s the lack of experience in saying something like that in your mother tongue or a specific cultural dynamic. So I was really interested in investigating more about this term and relating to sort of the experience of, sort of like, I think going in between these two countries and how I feel within this physical body of mine. I think being a plus size Asian woman, how that sort of I just wanted to relate the experience of how metaphorically and literally when you feel like your body does not belong, how that relates to maybe the concept of mother tongue shame.

And so I’m at the very beginning stage of this, but I’m interested in… this is kind of the next project that I’m interested in exploring. And I’ve been thinking about making dolls and putting little screens in dolls. And I think that’s just a super preliminary idea for now.

HM: I do know what it’s like to be in a culture, or part of cultures where our bodies are expected to be a particular size or shape, and we don’t all fit that societal expectation. So I think it would be interesting to see how that idea of yours evolves and kind of how it really comes out… Y’know I forgot to ask you if your parents have seen Red Threads, and what that was like.

YM: At Slamdance, it was my mom’s first time seeing it and it was really special because she flew in from China to meet me in Utah and it was the first time we saw each other in person in three years because of the pandemic visa and all that stuff.

And so it was really special to (a) reunite with her after so long and (b) show her this piece, even though they had asked me to send it to them before. But I’ve always been really afraid and I just didn’t know what they would think about the way I was sort of talking about my relationship to home. And then also my parents are both artists and so artists who I really respect and was really influenced by, and so I think other fear of if they think it’s not good, then that really for me is like it would feel really dooming. But I think that my mom apparently cried through the whole thing watching, which I guess is understandable because she is in it. She really liked the film, and so I think that’s good. In terms of my personal growth as a filmmaker, I think she has a lot of specific notes.

HM: But obviously she as your mom, it’s a completely different thing. So it’s kind of cool that they’re also developing respect for your art and appreciation for your art.

YM: I think so. I hope so. I guess that sounds really nice. So I’m glad she was there for the festival because I think just being part of that whole experience, it’s also really it kind of really brings it home. I think she also felt like because most of I think my film was maybe the only one with Chinese subtitles and the only one with Chinese characters on the poster… But she had told me that when she saw it on the street, she was really excited. She told like three strangers that this was her daughter’s film and she just felt really moved to see that in the sea of English words there was a small poster in Chinese that she could recognize and it was my film. And so when she spoke about that, I think I was very moved and again felt I think it reemphasized for me why it was important for me to make this for sure.

I enjoyed my conversation with Yuchi Ma. She is a truly talented artist, and so graciously shared details about her art work and approach to her art. You can follow more of Yuchi’s work on her instagram page.